Equality & Inclusion

ASEAN-ACT’s support for equality and inclusion is about removing obstacles faced by groups most affected by trafficking in persons.

Tackling entrenched attitudes, norms and behaviours in order to support victim-centred approach – regardless of gender – is challenging and will take sustained commitment and effort from all stakeholders.

We are committed to supporting partners in the region to better understand gender and other identity markers that intersect and impact on individual’s vulnerability to trafficking, and their experiences as a victim or witness.

This includes incorporating diverse voices in discussions on policies, laws and practices relating to trafficking, increasing the ability of trafficked victims to exercise the rights in the justice system and contribute to reform, and holding duty bearers to account in the elimination of discrimination and upholding the human rights of marginalised groups.

Stereotypes about victims of trafficking remain pervasive, with may many believing that trafficking only happens to women and girls. As a consequence men and boys who have been trafficked are often not identified as victims or once identified encounter challenges in accessing appropriate shelter and support.

We are bringing together counter-trafficking and disability advocates to dialogue and form partnerships to bridge the gap with the aim of reducing the vulnerabilities of persons with disabilities to trafficking, and strengthening justice and support for persons with disabilities who have been trafficked.

The diversity of minority groups – including women and girls, men and boys, LGBTQI, ethnic minorities, migrant and stateless people – reinforces the concept that each victim’s experiences of trafficking is unique and influenced by the particular markers of identity that combine and intersect to produce vulnerability to trafficking.

All diversity groups face barriers in accessing services and legal redress, but their experience of exclusion varies substantially from group to group and even between individuals.

We have supported research to better understand vulnerability to trafficking. And we working with partners in the region with projects and activities to better understand diversity and address these barriers, supporting ASEAN Member States can effectively implement their ACTIP obligations.

The ACTIP reinforces a commitment to victim-centred and rights-based approaches with a particular focus on women and children. And recognises the link between gender equality and trafficking, calling for more efficient investigations and prosecutions, and effective support for victims and witnesses.

The Bohol TIP Work Plan 2.0 provides a roadmap for the implementation of the ACTIP and the ASEAN Plan of Action against TIP, adopting gender-responsive approaches.

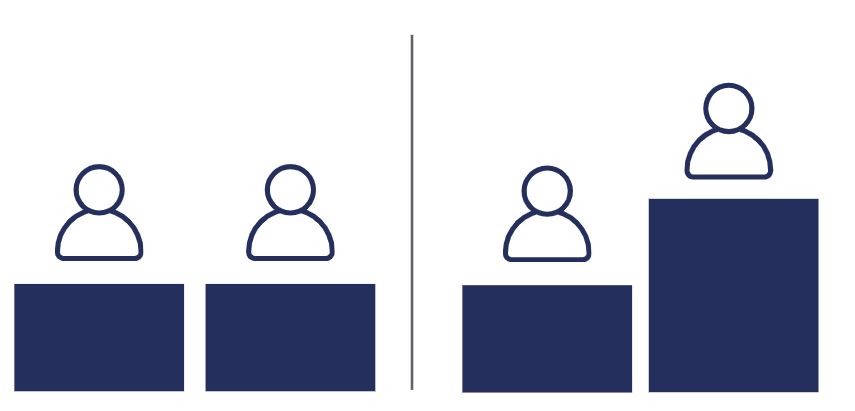

What is the difference between equality and equity?

Although used interchangeably, gender equality and gender equity are terms with distinct meanings. Gender equality provides the same opportunities, rights and responsibilities to all genders with a focus on ensuring everyone has the same starting point and is treated equally.

Gender equity recognises the different needs and circumstances of different genders, which may require different resources and opportunities to achieve fair outcomes. Gender equity aims to level the playing field by addressing social disadvantages by providing additional support.

What is gender mainstreaming?

Gender mainstreaming is a strategy to address gender disparities and gaps by integrating gender dimensions in the analysis, design, implementation and monitoring of projects and activities. In addition to ensuring gender considerations are integrated throughout all aspects of design and deliver, it also aims to challenge believe systems that shape discrimination and that perpetuate inequality. Effective gender mainstreaming relies on access to data, expertise, analysis, budget, resources and a culture of change.

Women and girls

According to the UNODC 2018 Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, women account for two-thirds of the detected victims of trafficking in East Asia and the Pacific. Of those detected, 60% were trafficked for sexual exploitation and 38% were trafficked for forced labour.

Women comprise the majority of victims, but women are also often the recruiters – it is not uncommon for the recruiters to be former trafficking victims, or someone known to the victim.

In recent years, there has also been an increase in reported cases of women and girls being trafficked into domestic work and forced marriages. “Bride trafficking” from countries such as Cambodia, Indonesia, Myanmar, Lao PDR, and Vietnam to China is increasing, in part due to China’s gender imbalance.

Men and boys

Gender-related barriers and risks faced by male victims of trafficking are not well understood or accommodated. A significant part of the problem is the widely held societal belief that males are perpetrators and not victims.

In the Greater Mekong region, men and boys comprise nearly two-thirds of trafficked and forced labourers in low-skilled labour sectors, including fishing, agriculture and factory work.

As these men and boys tend to work in unregulated jobs in high-risk sectors, they are particularly vulnerable to abuse and extreme occupational hazards.

According to UNODC’s 2022 Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, the percentage of boys identified as victims of human trafficking more than quintupled between 2004 and 2020.

Gendered expectations on men as financially responsible for their families, and stereotypes that men are not trafficked, mean that male victims may not self-identify as victims.

Men may be forced into labour through debt-based coercion, passport confiscation, threats of physical or financial harm, or fraudulent recruitment. Male victims of trafficking may also be arrested and prosecuted for the unlawful acts their traffickers compelled them to engage in.

People living with disability

One billion people worldwide experience some form of disability, with disability prevalence rates usually higher in developing countries. Almost 60% of those with disability live in Asia and the Pacific.

Disability and trafficking intersect in two main ways – persons with disabilities may become victims of trafficking, or victims may acquire a disability as a result of being trafficked.

Persons with disabilities may also face a range of physical and communication challenges and attitudinal barriers when accessing justice, and may be overlooked as credible witnesses.

To address gaps in data between disability and trafficking, our research in partnership with Australian University La Trobe enquires into the vulnerability of persons with disabilities to trafficking in persons, as well as the barriers victim/survivors with disabilities face when accessing remedies, justice and support.

Watch this animation explaining the nexus between disability and trafficking

Ethnic minorities

Trafficking victims in Southeast Asia tend to be young, poor and ethnically diverse. Young women and girls aged 15 to 25 from ethnic minority groups such as Mon-Khmer and Tibeto-Burman groups in the border areas of Thailand are disproportionately represented in statistics on victims of trafficking. Khmu girls from the northern provinces of Lao PDR have been identified as the majority of victims of trafficking for forced marriage into China and Thailand.

Ethnicity, when coupled with geographic isolation, poverty, gender and limited education, increases the vulnerability of many ethnic minority groups in the region to trafficking, especially trafficking for marriage, sex work and labour. Ethnic minorities may be further disadvantaged when trying to access justice systems and support services due to their limited education, language differences or prejudice and discrimination from officials.

Migrants and stateless people

Migrants and stateless people face obstacles when accessing support services and justice systems due to their lack of citizenship or identification documents and their inability to speak the local language.

Stateless people, especially men without work opportunities and official paperwork, are more likely to take risks associated with labour migration and are vulnerable to human trafficking.

In Myanmar, the Rohingya, Rakhine, Shan and Kachin communities have an increased risk of trafficking due to internal displacement and conflict.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex people

Without strong support networks and access to government services, LGBTQI people may be excluded from their communities and fall through the cracks of society – making them easy targets for human traffickers.

At the same time, as victims of trafficking they may face discrimination and bias when navigating the justice system and accessing victim support services.

For example in the region, law enforcement may stigmatise and sometimes criminalise LGBTQI people victims or witnesses, which makes it almost impossible for them to come forward. The diversity of these groups reinforces the concept that each victim’s experience of trafficking is unique and influenced by the particular markers of identity that combine and intersect to produce vulnerability to trafficking.